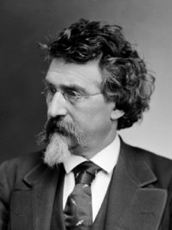

Mr. Mathew B. Brady decided at the age of 20 that he would devote his life to the new profession of photography. He moved to New York City and studied under the skilled daguerreotypist Samuel F.B. Morse. By 1844, he had his own photography studio in New York, and by 1845, Brady began to exhibit his portraits of famous Americans. Brady photographed 18 of the 19 American Presidents from John Quincy Adams to William McKinley. The exception was the 9th President, William Henry Harrison, who died in office three years before Brady started his Photographic Collection.

On February 27, 1860, Abraham Lincoln arrived in New York City to give an address to members of the Republican Party meeting at Cooper Union. Lincoln proceeded directly from the railroad station to Brady’s studio where he posed for his portrait. That evening his speech impressed the news media and the next day nearly every newspaper in the city printed a copy of Lincoln’s speech along with the photograph Mathew Brady’s had just taken of the gentleman from Illinois. Historians believe that Lincoln’s speech won him the presidential nomination and Brady’s portrait of Lincoln won him the election. Brady also photographed Abraham Lincoln on many other occasions in his Washington D.C. studio. His Lincoln photographs have been used for the $5 dollar bill and the Lincoln penny.

It was Mathew Brady's efforts to document both the Union and Confederate Armies that earned Brady his place in history. Despite the obvious dangers, financial risk, and discouragement of his friends, Brady was later quoted as saying "I had to go. A spirit in my feet said 'Go,' and I went." His first popular photographs of the conflict were of the First Battle of Bull Run, in which he got so close to the action that he barely avoided being captured. He employed Alexander Gardner, James Gardner, and seventeen other men, each of whom was given a camera and a traveling darkroom. They were instructed to take photographs wherever possible. Brady generally stayed in Washington, D.C., organizing his assistants and rarely visited the battlefields personally. This may have been due, at least in part, to the fact that Brady's eyesight had begun to deteriorate. In October 1862, Brady presented an exhibition of photographs from the Battle of Antietam in his New York gallery entitled, "The Dead of Antietam." Many of the images in this presentation were graphic photographs of corpses, a presentation totally new to America. This was the first time that families back home saw the realities of war which differed from their previous conceptions from "artists' impressions".

Following the conflict, a war-weary public lost interest in seeing photos of dead bodies. Mathew Brady’s practice declined drastically and he went deeply in debt. When the U.S. government refused to buy his 10,000 photographic glass plates, he was forced to sell his New York City studio and go into bankruptcy. In his later years he was very

depressed by his financial situation, by his loss of eyesight due to the handling of photographic chemicals, and by the death of his wife in 1887. Mathew Brady died penniless in the charity ward of the Presbyterian Hospital in New York City on January 15, 1896, from complications following a streetcar accident. Brady's funeral was financed by veterans of the 7th New York Infantry and was followed by his burial in the Congressional Cemetery in Washington, D.C.

Brady’s Tombstone

Editor’s Comments: Most persons do not think of Mr. Brady as an entrepreneur, however, it was photographer Mathew Brady who first had the idea of photographing the Civil War. He reasoned that the public would be interested in buying his photographs. Today much of what we

know about the Civil War has come from Mr. Brady’s photographs.